Pixboy

No sooner had I put down The Adventures of Elena Temple than my eye — still looking out through retro-tinted glasses — was caught by PixBoy.

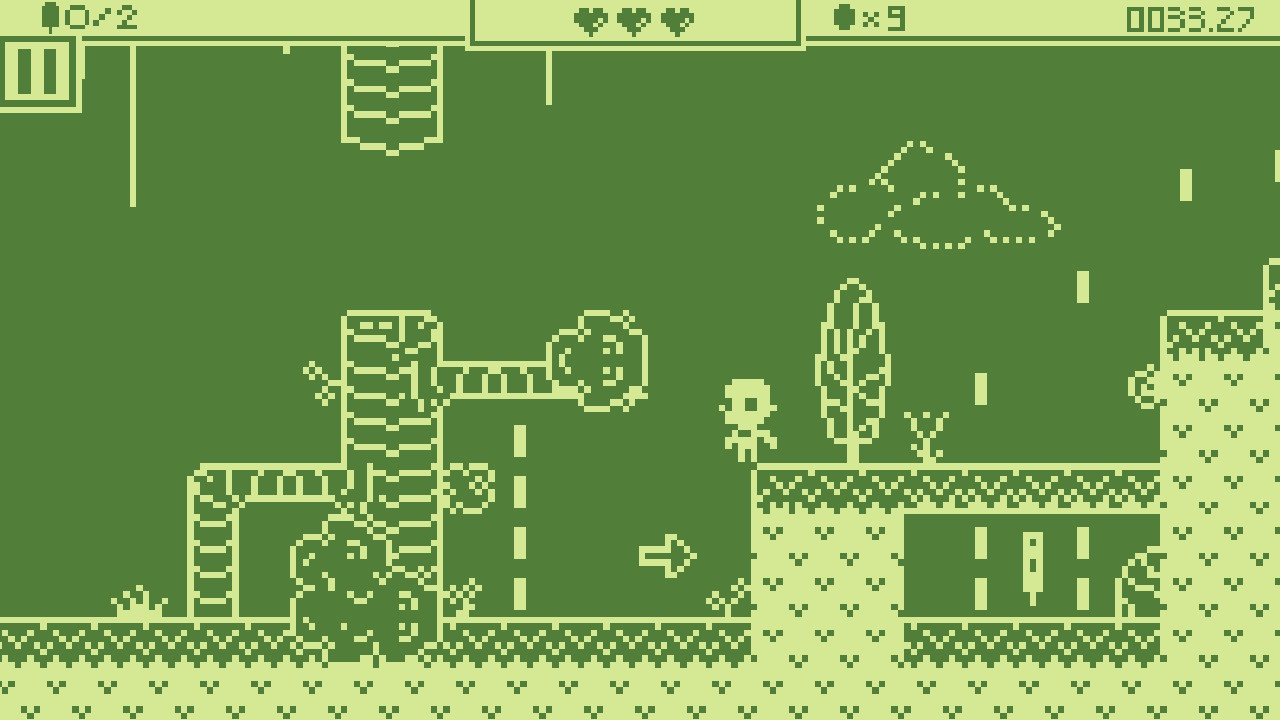

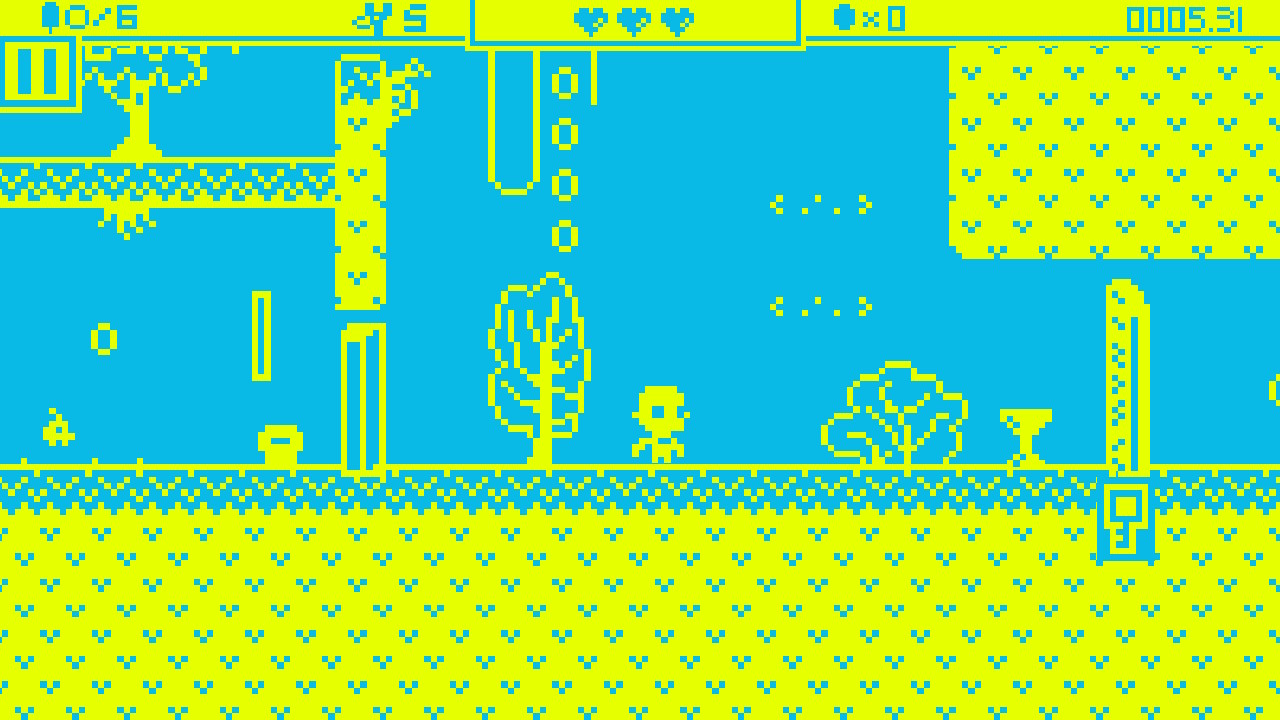

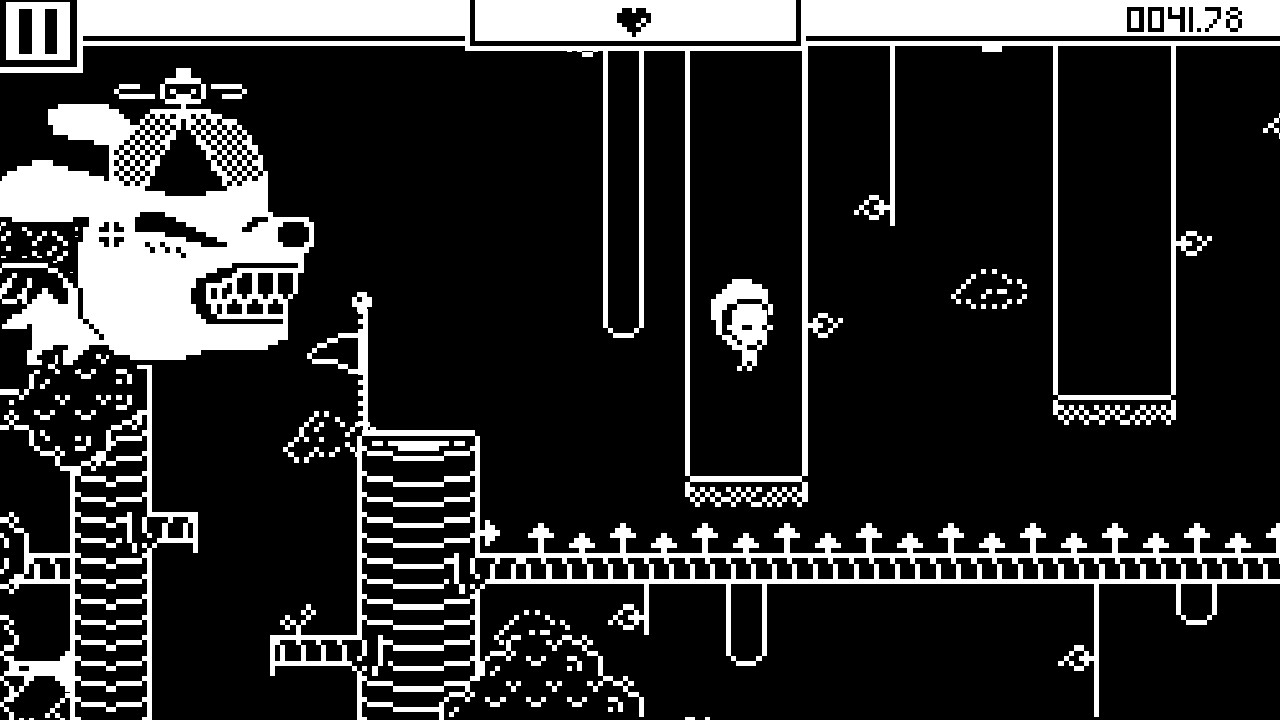

What struck me initially was the stunning use of two-colour graphics, not just in the main sprite and primary platforming objects, but also the backgrounds, enemies, and bosses too — everything here is rendered in just two colours, with big chunky pixels, and it all looks beautiful.

Too often, games that use very restricted colour palettes and/or resolutions suffer from a common problem: conveying function. Heck, it’s a problem that can plague any platformer, but in particular those with less detail. Most obviously, this manifests in whether a specific element is ‘active’, in the foreground, and can be interacted with or whether it’s just background detail which can safely be ignored.

Pixboy manages to create a clear distinction and makes it look effortless. Almost everything that can be interacted with moves. Almost every platforming object is either obvious in context, or reliably ‘solid’ enough to identify. The different palettes, despite offering the smallest amount of difference imaginable, each somehow feel different — I suppose this is quite considerably due to associations between the colours and the gaming systems they represent.

Apart from the usual, the mechanic that sets this game aside is the ‘soar’, a very low-gravity fall which allows for plenty of movement. It’s a bit like the float mechanic provided by Mario’s cape or raccoon tail, without any of the additional flying mechanics, but permanently available. A skilled combination of normal fall and float is required to tackle some of the enemies present: although the standard ‘jump on head’ move has been faithfully borrowed, it’s made slightly trickier by the small size of some of the creatures that can do you harm.

Also armed with a rudimentary catapult, Pixboy’s challenge is, predictably, to reach the end point of each scrolling level, avoiding or killing enemies as he goes. There are four worlds with 10 levels in each, the last level of each world featuring a boss. Early levels can be completed in 15–30 seconds, but later ones clock-in at a few minutes each.

Everything feels right. The standard jump — although it’s paired with a very slow fall, even when not floating — is variable and smooth. None of the enemies or obstacles feel unfairly difficult, and all the secret areas or locked rooms can be solved easily, with enough effort required to add variety to the overall experience. Plenty of classic elements are present — you know the ones: disappearing platforms, spikes on rotating tiles. There are a few more unusual mechanisms such as the conveyer belts (?) which you fall through unless jumping, in which case they’ll propel you upwards. But everything is accessible enough to make Pixboy feel like a game within everyone’s grasp.

The result is something very much like a top-notch Game Boy platformer: think Duck Tales, Gargoyle’s Quest. I actually felt a heavy Super Mario Land vibe, although Pixboy is much more interesting in terms of overall level design — this isn’t just about running left-to-right all the time! It also reminded me of certain old Spectrum games — the two-tone palette no doubt reinforces this — and this kind of resolution certainly suits handheld gameplay very nicely indeed. But it’s so much more polished than the Spectrum or Game Boy games I remember. Partly that’s down to level design, but there are also two key aspects here which really go a long way in making Pixboy the game that it is.

First, the game adopts a modern approach to lives, in which each level is self-contained. There’s no need to complete everything in one run, so the player is free to experiment and take risks at their own pace. There’s even an abundance of free lives to pick up in each level, so even the toughest can be quite forgiving. Although I started quite slowly, by the time I got into the late-game, it was pretty quick to complete: you might only get 2 or 3 hours out of that core challenge.

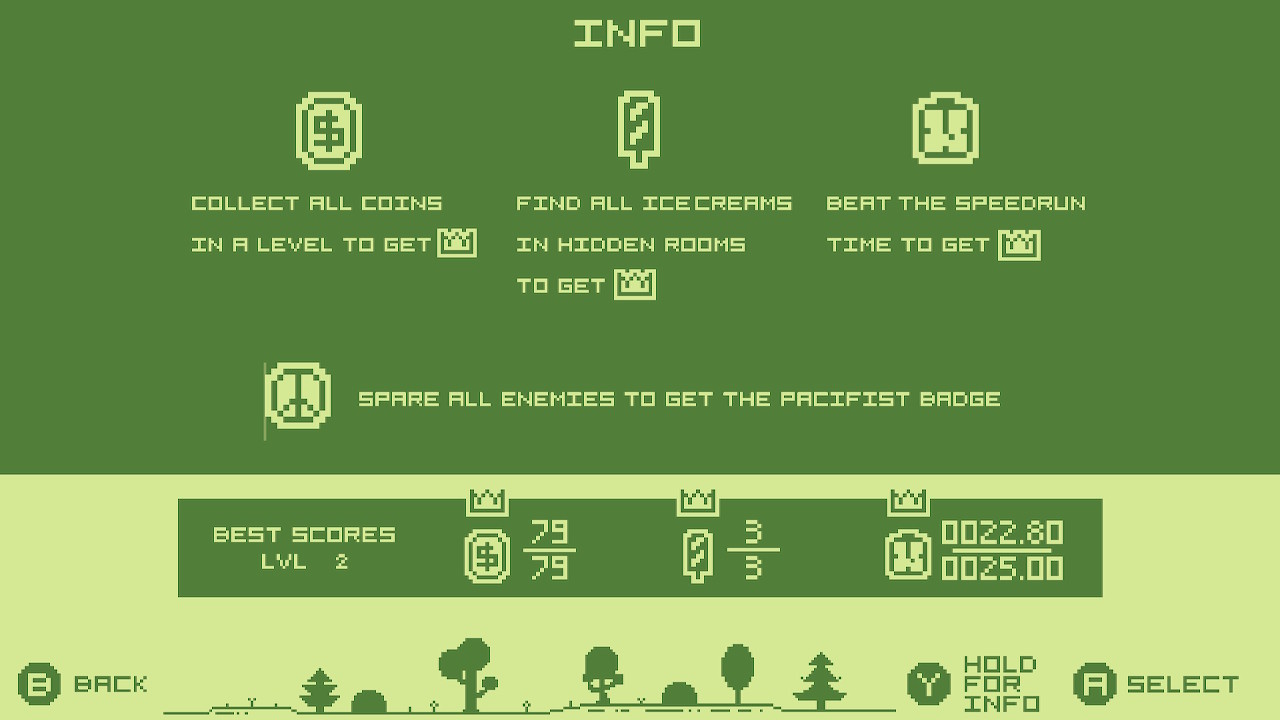

But here’s the other difference: again, in a more modern take on the genre, each level is not just for getting through. There are effectively four additional challenges for each of the 40 levels here: collect all coins, collect all hidden ice lollies, speedrun, and ‘pacifist’ — don’t kill anything! The only small flaw I found here is that the ‘ice lolly’ challenge, which requires discovering secret rooms, is made somewhat redundant by the coin challenge since those rooms always contain coins too.

Verdict

😃

Of all the games that claim to cater for lovers of retro gaming, Pixboy is possibly the one that has felt the most satisfying to me recently. Both in terms of how well it replicates an original experience, but also how good it feels to play as a game today. It doesn’t really offer anything new, but the attention to detail and overall design make this a very fun game indeed. There might only be 40 levels here, but they are great to play, and Pixboy offers a huge amount of replayability.

I played Pixboy for about 5 hours and there’s still more time to be had, going back and completing all four challenges on each level. It’s perfect for handheld play.

I paid £4.04 for Pixboy on release day; the game is normally priced at £4.49. This is an absolute bargain.