The Adventures of Elena Temple

A long time ago, in a galaxy surprisingly similar to our own (just with some consoles that don’t actually exist) a developer made a game and kept trying to sell it on different systems. They tried the exact same game — other than colour palette changes — on seven different consoles and computers, and the game failed every time. So, … er … here’s … that game, again.

… or so the story goes. For none of this is actually, you know, real. But it’s still a weird backstory, right? To be fair, the game supposedly failed because the consoles failed, but that sounds like a workman blaming his tools, to me. Thankfully, the ‘game of the game’ has been released on some modern platforms that actually exist, and the Nintendo Switch is one of them.

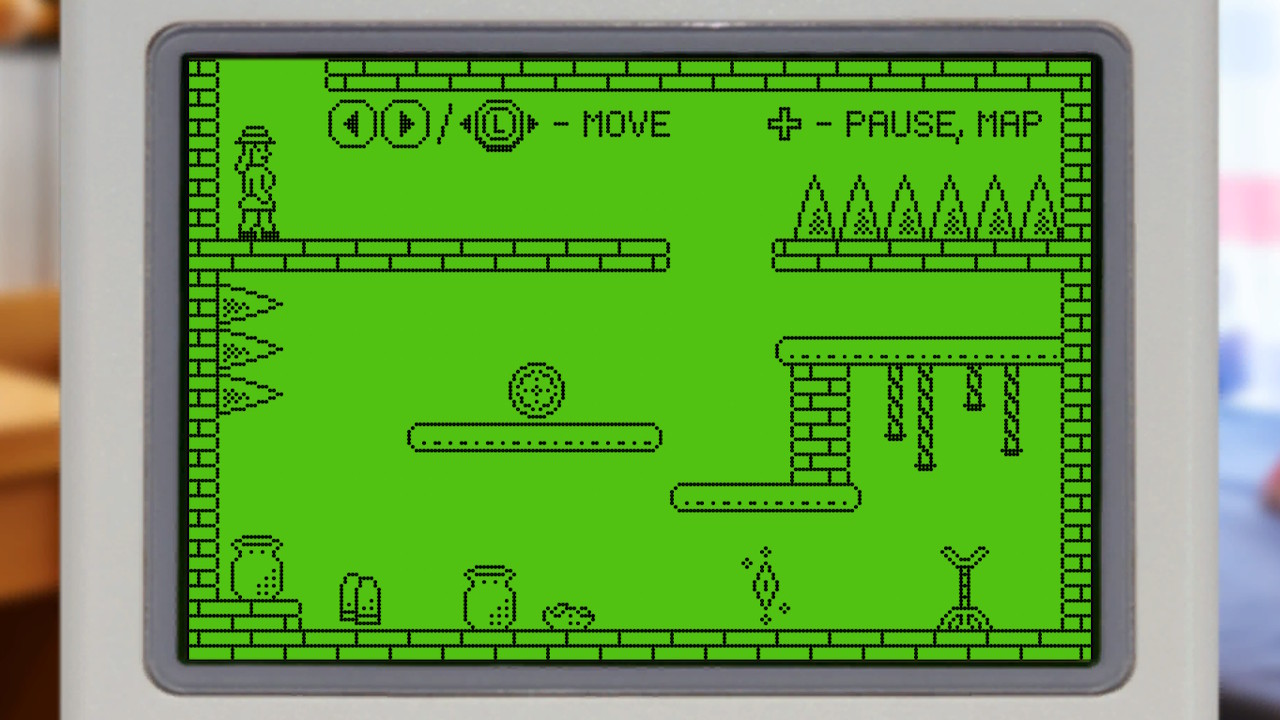

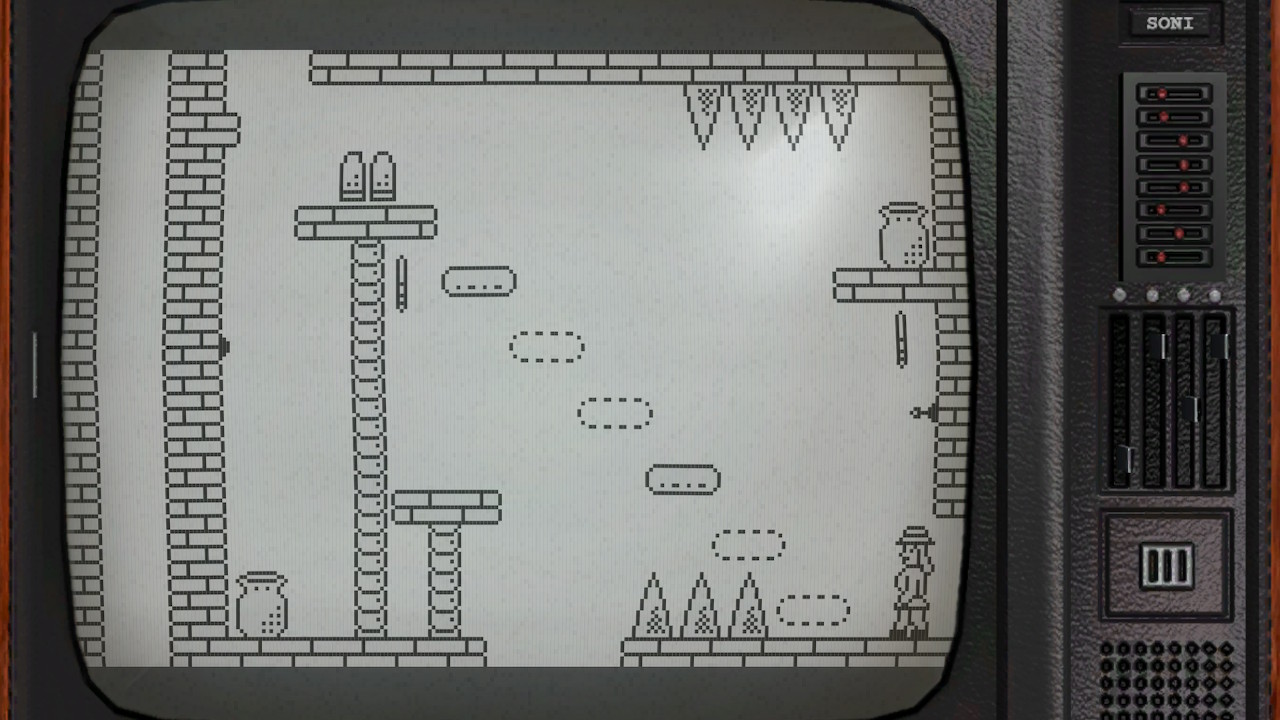

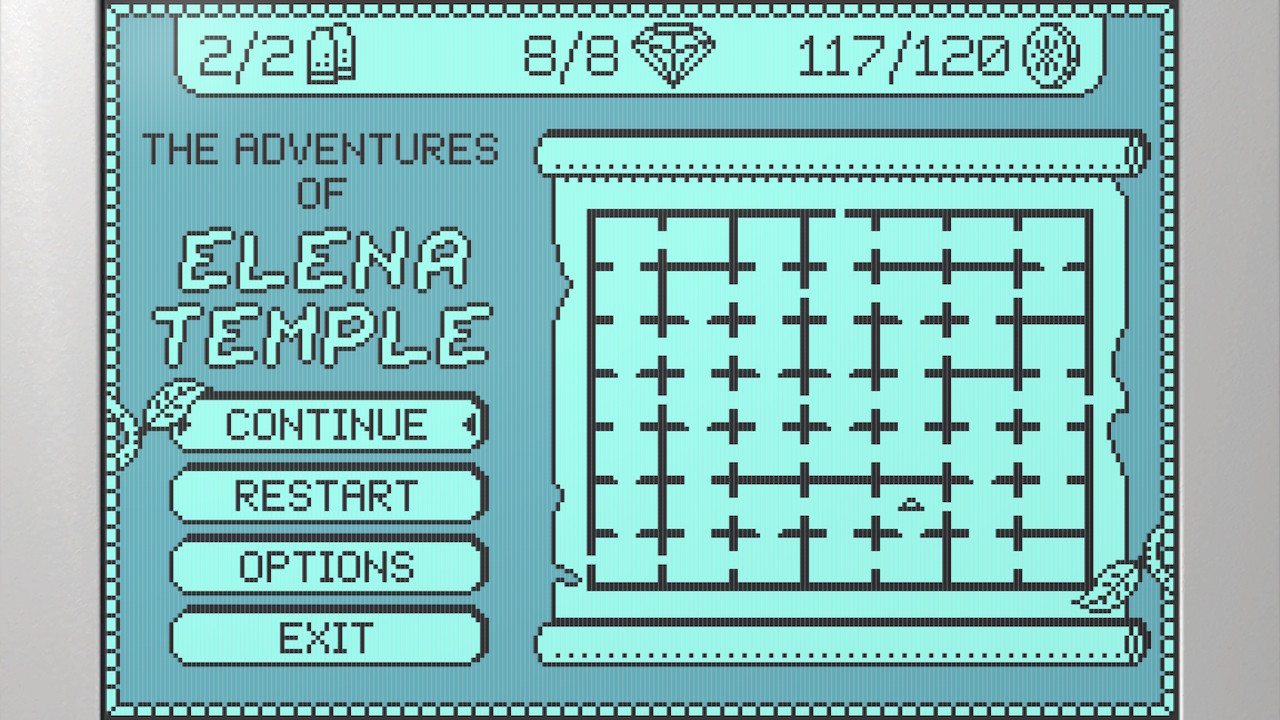

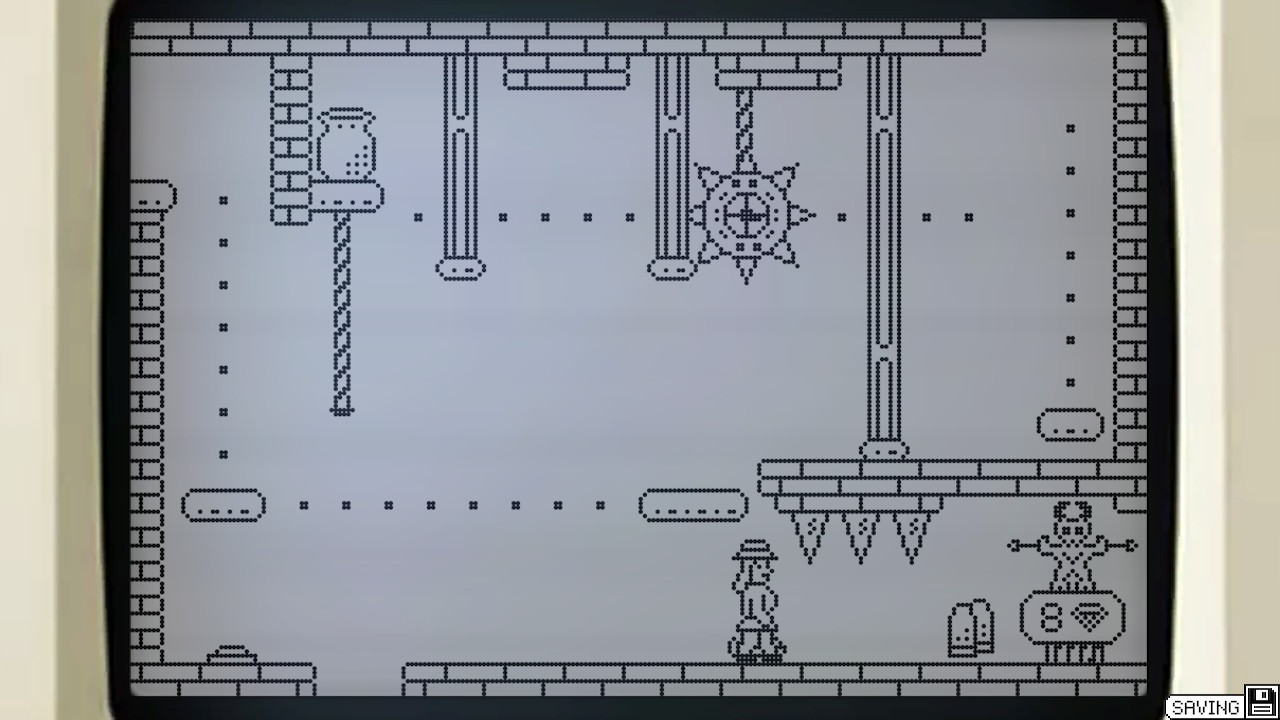

Several low-colour indie games have made good use of palette-switching as an in-game collectible: Dig Dog, Gato Roboto, and Downwell are three notable examples. The Adventures of Elena Temple takes this one step further and bakes in customisable palettes right from the outset, framing it as an integral part of the fictional story surrounding the game’s development. Each palette represents a different ‘emulated console’, the selection of which also controls the surrounding screen decoration. It’s a decent idea, and avoids the issue of only discovering a palette very late into the game — something that is less of a problem for the roguelikes mentioned.

It also helps, along with the plotline, to set the scene — Elena Temple is a game designed primarily to rekindle memories of actually playing on these kinds of system, the 8-bit wonders of yesteryear. And pretty much every aspect of the game does that, warts and all. Graphics, sound, gameplay, bugs: they’re all straight outta the eighties.

Elena Temple plays like a metroidvania-lite, with a gloriously nostalgic ‘single-screen rooms in a 2d grid’ layout. Most of these rooms play like self-contained puzzles or feature tough platforming challenges and the map is full of collectibles, secret pathways, and optional challenges.

Although the jump feels awkward by today’s standards — it’s fixed-height, very low-gravity, and very slow — it feels like a pretty accurate recreation of an 8-bit game and the overall style strongly reminded me of the Game Boy. Obviously, the Game Boy-themed palette helps reinforce that. The game features many classic platforming elements including retracting spikes, collapsing platforms, and buttons to push or (hint) shoot at.

The joy here is in the little things: the tight jumps, the restricted combat, the overall design and these small details work well together. It’s a very ‘particular’ type of gameplay which, to some extent, the player must resign themselves to, but that kind of co-operation will be rewarded with a fun challenge.

The main game offers a lot for completionists, too, and I was engaged enough to get all the stuff. It took a while because I just missed a couple of solutions that seem obvious looking back, but it was still fun unearthing every last item. There’s a long list of achievements to reward repeat runs.

Some of the power-ups can — as advertised — slightly break the game, but there are also some bugs that can halt a run, too which is disappointing. I once got stuck spawning in a place where I ended up between spikes on either side of me, with no means of progress other than dying and repeating the whole thing endlessly. An abandoned run, that was.

So, anyone looking for a nostalgia kick will be served very well here but, of course, the problem then becomes how well new, modern-day players are catered for. I’m very much in favour of mining ideas from the past — single-screen rooms, for example — and exploring how they can fit into gaming in the twenty-first century. Too many concepts from the olden days have been abandoned simply due to an association with the past rather than for any meaningful reason. Just because a certain feature was borne from technical limitations, doesn’t mean it cannot have any merit with appropriate amounts of polish.

Sadly, Elena Temple doesn’t really go out of its way to do anything radical. It faithfully reproduces a style of game from forty years ago, without really bringing anything new to the table. It results in something that is totally believable as a ‘long lost treasure’, but not the kind of game that will have a lot of fans outside of the nostalgia set.

Verdict

🙂

I enjoyed playing Elena Temple for the most part, once I got accustomed to the strange movement, and learnt how combat and collection mechanisms worked. It was very enjoyable from the perspective of someone who remembers a time when all games really were like this. But nostaliga has its limits, and many will be underwhelmed with the primitive graphics, basic gameplay, and lack of any more significant follow-through on the whole ‘virtual console’ concept. Still, for the price and added bonus of playing this handheld, you could certainly do a lot worse.

I’ve played Elena Temple for 5 hours, some of that handheld. A review code was graciously provided by the developer, GrimTalin. The game is available for the very affordable price of £4.49.